Non Coding Variant Effect Prediction using Basenji

Predicting the causal variants is of one of the challenging problems. This blog discusses the model, Basenji which can prioritize the causal variants.

Introduction

Human DNA is about 99.5% identical from person to person. However, there are small differences that make each person unique. These differences are called variants. Some of these genetic variants are common, such as the variants for blood types (A, B, AB, or O), while many of the variants are rare, seen in only a few people. And a few among these variants would be associated with the disease risk. By predicting these disease-associated variants, we would get to know what exactly is driving the disease and come out with the right kind of treatment.

Variants are of two types, Coding and Non-coding.

Coding DNA: The DNA which encodes the proteins are called coding DNA. This Coding DNA is responsible for transcription and translation.

Non Coding DNA: DNA which do not encode proteins are called Non-coding DNA. They perform very important functions which include regulating transcription and translation, producing different types of RNA such as microRNA and protecting the ends of chromosomes.

To understand the genetic basis of disease, we need to understand the impact of variants across the genome.

Why Non Coding Variants?

Only about 1 percent of DNA is made up of protein-coding genes; the other 99 percent is non-coding. Scientists once thought non-coding DNA was “junk,” with no known purpose. However, it is becoming clear that some are integral for the proper functioning of cells. Mostly, the control of gene activity and the majority of the diseases are caused by these non-coding variants.

Predicting the effects of non-coding variants

We need to build models that can predict molecular phenotypes directly from biological sequences to probe the association between the phenotype and the genetic variation.

Thus, sequence-based deep learning models can be used for assessing the impact of such variants which offer a promising approach to find potential drivers of complex phenotypes.

In this blog, we will learn about one such sequence-based on deep learning model, Basenji .

Basenji

Models for predicting phenotypic outcomes from genotypes have important applications for understanding the genomic function and improving human health. Basenji is a machine-learning system to predict cell-type-specific epigenetic and transcriptional profiles in large mammalian genomes from DNA sequence alone.

Numerous lines of evidence suggest that many non-coding variants influence traits by changing gene expression. Thus, gene expression offers a tractable intermediate phenotype for which improved modeling would have great value.

Model Structure

What distinguishes Basenji from others is that it uses convolutional neural networks. This system identifies promoters and distal regulatory elements and synthesizes their content to make effective gene expression predictions. The distal regulatory elements play an important role in controlling gene expression. So, this model predicts those regulatory elements and also provides information on how these elements influence the gene expression.

Input:

The model accepts much larger ($2^{17}$) 131-kb regions as input i.e, the entire DNA sequence. DNA sequences come in to the model one hot encoded to four rows representing the four nucleobases, A, C, G, and T.

Architecture:

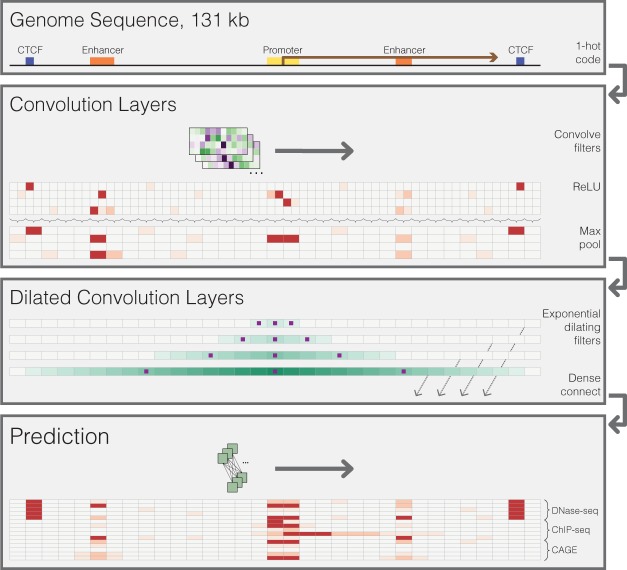

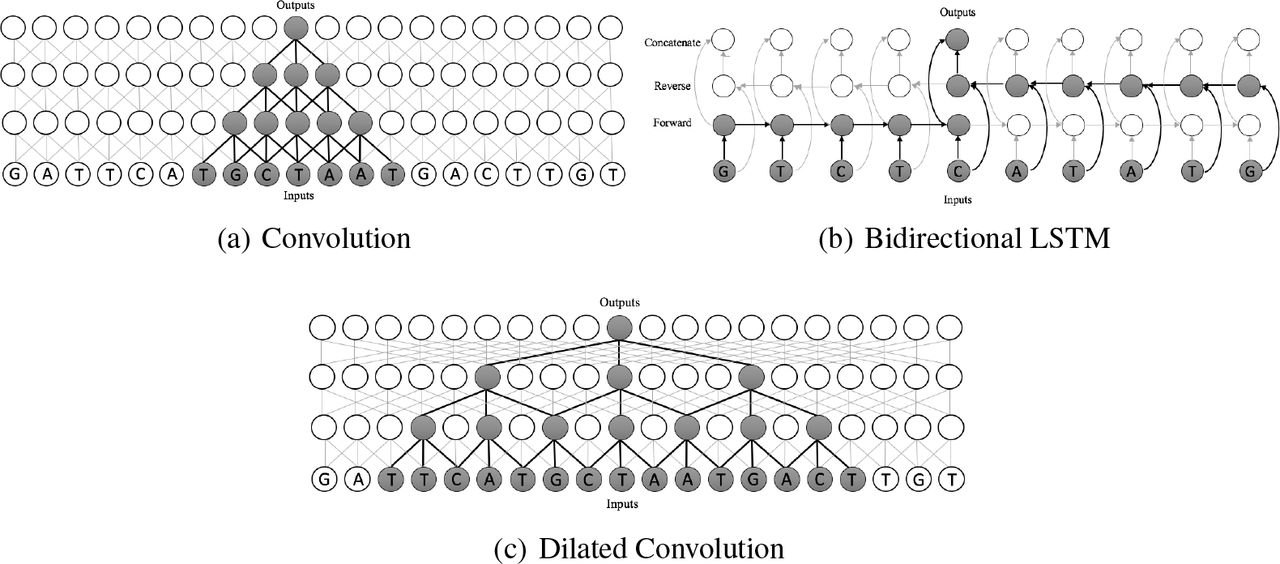

Basenji is a deep convolutional neural network with three layers i.e, Convolution, Dilated convolution and Prediction layers. Let us discuss these layers in detail.

a.Convolution layers:

It performs multiple layers of convolution and pooling to transform the DNA into a sequence of vectors representing 128-bp regions. We used a Basenji architecture with four standard convolution layers, pooling in between layers by two, four, four, and four to a multiplicative total of 128.

By these convolution layers, it observes the patterns in the DNA sequence and transforms the DNA into a set of vectors where each vector represents a 128 bp region.

b.Dilated Convolution layers:

These 128 bp regions which we obtain after the convolution layers would be fed as input to the dilated convolution layers.

To share information across long distances, we apply several layers of densely connected dilated convolutions. After these layers, each 128-bp region aligns to a vector that considers the relevant regulatory elements across a large span of sequence.

The main aim of these dilated convolutions in our model is to view distal regulatory elements which are at distances, achieving a 32-kb receptive field width. It means, it extracts and combines the feature which is even farther from the TSS(Transcription Start Site).</p><p>

From the above image, we can see how the dilated convolutions, unlike standard convolutions, look at the patterns which are at distances. They combine those distant features to predict the distal regulatory elements and their effects on gene expression. Now let’s discuss the effects of distal regulatory elements and how they can be predicted in detail.

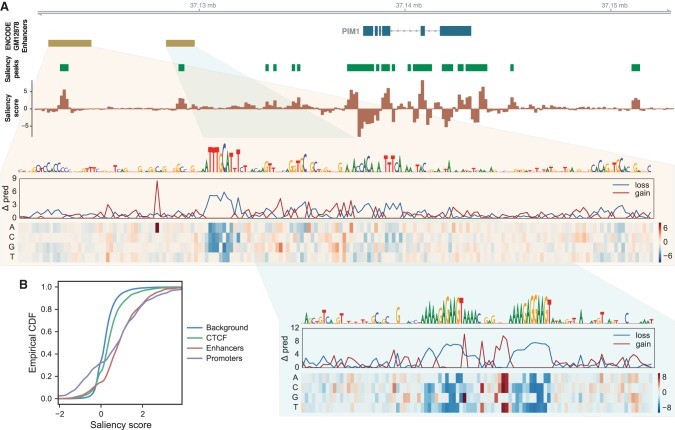

Predicting the effects of distal regulatory elements:

Distant enhancer sequences play a significant role in activating gene expression. We devised a method to quantify how distal sequence influences a Basenji model’s predictions and applied it to produce saliency maps for gene regions. The saliency scores are calculated for all the 128 bp regions which we get after the convolution layers and before the dilated convolutions share the information. And these scores can be calculated as shown below:

</figure>

In the above image, we can see the peaks in the saliency maps and peaks in this saliency score detect distal regulatory elements, and its sign indicates enhancing (+) versus silencing (−) influence. The promoter region has extreme saliency scores, including repressive segments. In short, this means, mutating the regulatory sequence recognized by the model in these regions would increase the predicted

activity.

Intriguingly, promoters have more extreme scores at both the high and low ends, suggesting that they frequently contain

repressive segments that may serve to tune the gene’s expression rate. This feature is also present for enhancers, but at a far lesser magnitude on the repressive end.

c.Prediction Layer:

Finally, we apply a final width-one convolutional layer to parameterize a multitask Poisson regression on normalized counts of aligned reads to that region for every data set provided and it predicts the 4229 coverage datasets.

This is the architecture I have implemented:

import numpy as np

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

class Basenji(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super(Basenji,self).__init__()

self.conv_net=nn.Sequential(

nn.Conv2d(4,128,(20,1)),

nn.BatchNorm2d(128),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.MaxPool2d((2,1),(2,1)),

nn.Conv2d(128,128,(7,1)),

nn.BatchNorm2d(128),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.MaxPool2d((4,1),(4,1)),

nn.Conv2d(128,192,(7,1)),

nn.BatchNorm2d(192),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.MaxPool2d((4,1),(4,1)),

nn.Conv2d(192,256,(7,1)),

nn.BatchNorm2d(256),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.MaxPool2d((4,1),(4,1)),

nn.Conv2d(256,256,(3,1),dilation=(1,1)),

nn.BatchNorm2d(256),

nn.ReLU(),)

self.dilation1=nn.Sequential(

nn.Conv2d(256,32,(3,1),dilation=(2,1)),

nn.BatchNorm2d(32),

nn.ReLU(),)

self.dilation2=nn.Sequential(

nn.Conv2d(256,32,(3,1),dilation=(4,1)),

nn.BatchNorm2d(32),

nn.ReLU(),)

self.dilation3=nn.Sequential(

nn.Conv2d(256,32,(3,1),dilation=(8,1)),

nn.BatchNorm2d(32),

nn.ReLU(),)

self.dilation4=nn.Sequential(

nn.Conv2d(256,32,(3,1),dilation=(16,1)),

nn.BatchNorm2d(32),

nn.ReLU(),)

self.dilation5=nn.Sequential(

nn.Conv2d(256,32,(3,1),dilation=(32,1)),

nn.BatchNorm2d(32),

nn.ReLU(),)

self.dilation6=nn.Sequential(

nn.Conv2d(256,32,(3,1),dilation=(64,1)),

nn.BatchNorm2d(32),

nn.ReLU(),)

self.prediction=nn.Sequential(

nn.Conv2d(192,384,(1,1)),

nn.BatchNorm2d(384),

nn.ReLU(),)

self.classifier=nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(1024,3),

nn.Dropout(0.1),

)

def forward(self,x):

out=self.conv_net(x)

out1=self.dilation1(out)

out2=self.dilation2(out1)

out3=self.dilation3(out2)

out4=self.dilation4(out3)

out5=self.dilation5(out4)

out6=self.dilation6(out5)

dense=torch.cat([out1,out2,out3,out4,out5,out6],1)

output=self.prediction(dense)

reshape_out=output.view(output.size(0), 384)

final=self.classifier(reshape_out)

return final

def criterion():

return nn.MSELoss()

def get_optimizer():

return (torch.optim.Adam,{"lr" : 0.002 , "betas" : (0.97,0.98) , "weight_decay" : 1e-6} )

Output:

The model’s ultimate goal is to predict read coverage in 128-bp bins across long chromosome sequences which would be then used to predict the regulatory activity function.

Usage of these predicted coverage values:

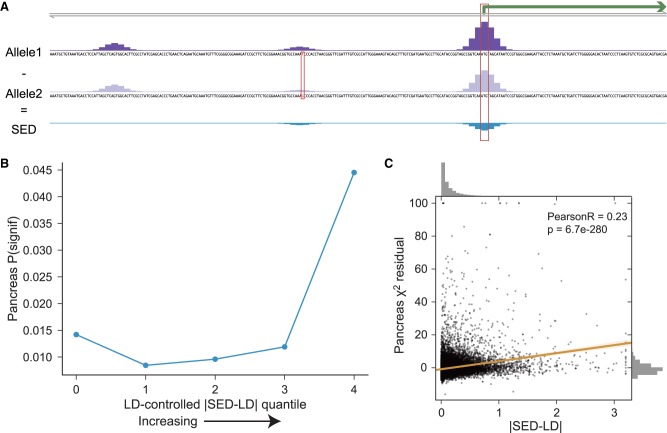

Disease-associated loci

Coverage tells the number of unique reads that include a given nucleotide in the reconstructed sequence.

Given an SNP–gene pair, we define its SNP expression difference (SED) score as the difference between the predicted CAGE coverage at that gene’s TSS (or summed across multiple alternative TSS) for the two alleles.</p><p>Basenji’s utility for analyzing human genomic variation goes beyond intermediate molecular phenotypes like eQTLs to downstream ones like physical traits and disease. With Basenji, a single experiment is sufficient to predict a genomic variant’s influence on gene expression in that cell type.

SED= | Allele1 - Allele2 |

Linkage disequilibrium(LD) is the non-random association of allele at a different loci in given population.By considering this |SED - LD| score, all the variants are ranked. And this gives the information about the causal variants i.e, based on the rank of the variants. Then these variants can be linked to disease loci and we can have knowledge about the genetic basis of the disease.

Summary:

So,this model can predict the causality of the variants and the person would be able to find the right treatment for his disease.